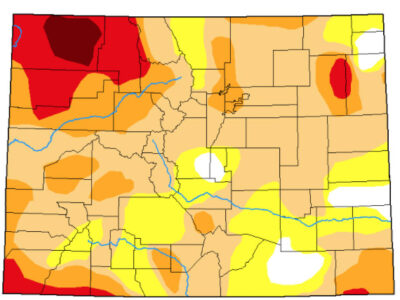

Colorado’s map from the Oct. 26, 2020, U.S. Drought Monitor looked like some kind of fresh hell, its swaths of red and orange highlighting what happens when there is too much heat and not enough water for a long time. Colorado’s resulting fire crisis had good company; much of the Western United States had similar stories of people running from their homes as the fires closed in.

Image/Tara Flanagan

It was so 2020, as further evidenced by the strain on the Colorado River and the ongoing wake-up calls in communities that receive its water – directly or diverted.

Locally, Chaffee County’s economies lean on supplemental summer releases into the Arkansas River. Despite two decades of drought and aridification, the Arkansas has been able to remain visually stunning in the high season – not entirely due to the workings of nature. It’s uncertain how that may change.

Colorado’s map with the U.S. Drought Monitor in late October, 2020, was awash in red and orange, depicting a dangerous and dry landscape. Image/U.S. Drought Monitor

One year later, the colors on Colorado’s map have softened to shades of beige and an innocuous-looking lemon-yellow, with darker spots remaining in the northwest corner and the far southwest edge. With some rain to its credit over this past summer and perhaps just plain luck, Colorado managed to escape the land-killing infernos such as the Cameron Peak Fire and the aptly named East Troublesome Fire of 2020.

Nobody knows exactly how those 2020 fires would have raged had not a major snowstorm rolled in on Oct. 25 last year and snuffed their trajectories. As it stood, East Troublesome charred 193,212 acres and 580 structures.

Snow is good. And traditionally it has been the utility player, if not hero, in the seven-state region served by the Colorado River, where, in a perfect world, it stores naturally on Colorado’s mountain peaks. Upon melting with a timed grace and running off in mid-spring, it flows south and west to the Gulf of California, serving some 40 million people en route.

Thanks to warmer temperatures and aridification, that sweet rhythm is off. Spring runoff gushes from the peaks too fast and sinks into the parched landscape before enough of it gets to its intended waterways.

Colorado’s image has tamed down in a year on the U.S. Drought Monitor, with Chaffee County’s current drought conditions depicted as moderate. Image/U.S. Drought Monitor

That said, later-season snows helped address an alarming dry trend in the spring of 2021, helping Chaffee County look better on the Drought Monitor and delighting those with fixations on the SNOTEL system and its high-country snowpack reports. The infusion of summer rain gave the appearance of a kinda-maybe monsoon pattern locally.

Water flowing through the Fry-Ark system, the trans-basin diversion from the Colorado River that flows out of the Frying Pan River in Pitkin County and which is released from Turquoise Lake and Twin Lakes, once again plumped the moneymaking waves in the Arkansas River from July 1 until mid-August this year.

Under the Voluntary Flow Management Program with the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District (SECWCD), 10,000 acre-feet of water is allocated during that time; moved to benefit recreation. All told, Fry-Ark sends out an average of 58,000 acre-feet each year, much of it going to agriculture below the Pueblo Reservoir.

It didn’t hurt that the Pueblo Board of Water Works was able to release 6,000 acre-feet from Clear Creek Reservoir early in the summer season. It echoed the cooperative dance of moving large amounts of water that has, by necessity, developed between water entities. This highlights the increased communication that is one of the upsides in the long-reaching, exhaustive conversations about water among an exhaustive list of stakeholders in Colorado and the West.

“It’s a team effort,” said Chaffee County Commissioner Greg Felt, who sits on numerous water boards in the state, including a governor’s appointment to the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “It’s really important to develop relationships.”

Chris Woodka, Senior Policy and Issues Management Manager with the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District, said the increasing pressures on water have caused groups to come to the table and seek solutions. “What’s different is we’re talking all the time with each other,” he said. “There was a time when people were wary of how other people were moving water. Everyone now realizes it’s to their advantage to talk.”

With water from Fry-Ark and Clear Creek Reservoir – not to mention rain, the fattened Arkansas River gurgled through the county once again and gave more than a passing nod to the local economies over the summer. Pandemic aside, things seemed nice and easy.

“It almost gives you a false sense of security,” Felt said, noting that with continuing drought and aridification, there are increasing signs of hydrological systems not being able to correct themselves.

“That whole program is built on Fry-Ark water,” he said. “There’s a lot at stake here. Diversions from the Fry-Ark project could be seriously impacted, and that’s a major concern.”

“It’s a no-brainer, probably, that a voluntary flow management program will be a lower priority than delivery for consumptive use,” he added.

Indeed, nothing is truly nice and easy anymore as the West faces challenges to just about everything that is known about water and how it continues to serve us.

Water planning has some good intentions, and that was evident in the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divided the region into upper and lower basins and determined the amount of water that needed to flow. For the record, that’s 15 million acre-feet per year, equally divided between the basins. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming comprise the upper states, while Arizona, Nevada and California, along with Mexico, comprise the lower portion.

The compact was a nice and necessary idea at the time, but it was done at a time when water flows were at their height. The Colorado River and its many diversions have benefitted people as far away as Denver and San Diego – well out of its direct course. In the Arkansas River Valley, seasonal diversions from the river have provided water when it is historically needed most, making more predictable seasons for agriculture, recreation and trout habitat, for example.

But with average temperatures in the Colorado River Basin running 2 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than in the 20th century, those original nice ideas are being retooled or sidelined in the name of badly needed, better ideas; addressing drought, aridification and salination, and how to feed people when the river can’t help so much anymore. A new plan for operating the Colorado River is due in 2026.

Featured image: The Arkansas River still looks strong in Chaffee County despite the challenges posed by drought and aridification. Image/Tara Flanagan

Editor’s Note: In late July, Gates Family Foundation and the Colorado News Collaborative awarded Ark Valley Voice (AVV) Journalist Tara Flanagan a water fellowship, to participate in a statewide newsroom effort to strengthen water reporting at newsrooms across Colorado. The Power of Water looks at the all-important role of the resource in people’s lives. The Series Will Continue…

Recent Comments