Tuesday’s hearing of the Subcommittee on Conservation, Climate, Forestry, and Natural Resources Hearing on Western Water Crisis was the First Since 2013

Colorado U.S. Senator Michael Bennet, Chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, released his opening statement ahead of the subcommittee’s hearing titled, “The Western Water Crisis: Confronting persistent drought and building resilience on our forests and farmland.”

This is the subcommittee’s first hearing since 2013, and the first since the subcommittee was expanded in 2021 to include attention to the impacts on climate.

Bennet’s opening statement as prepared is available below. Click here for a livestream of the hearing.

I call this hearing of the Subcommittee on Conservation, Climate, Forestry and Natural Resources to order.

Good morning everyone. I am pleased to call this Subcommittee Meeting on Conservation, Climate, Forestry, and Natural Resources to order.

I’m also grateful to Ranking Member Marshall for his partnership in organizing today’s hearing on Western water resilience. I know that he shares my concern about the unprecedented drought the West faces – especially as it relates to the declining water levels in the Ogallala Aquifer.

Our purpose this morning is simple: to sound the alarm about the water crisis in the American West.

The West hasn’t been this dry in 1,200 years.

1,200 years.

If we don’t get our act together in Washington, it’s going to not only put Western agriculture at risk, but the American West as we know it.

The Colorado River supplies the fast-shrinking Lake Mead. Image courtesy of Science Friday.

My state sits at the headwaters of the Colorado River, which starts as snowmelt in the Rockies before cutting across 1,400 miles to the Sea of Cortez.

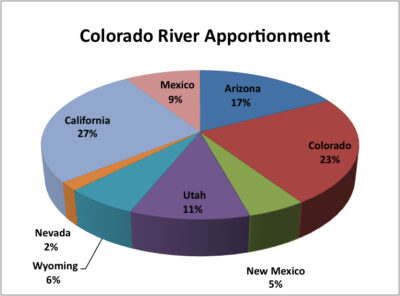

The Colorado River Basin is the lifeblood of the American Southwest. It provides the drinking water for 40 million people across seven states and 30 tribes. It irrigates five million acres of agricultural land. It underpins the West’s $26 billion outdoor recreation and tourism economy.

And it is running out of water.

The two largest reservoirs in the basin, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, are at the lowest levels since they were filled over 50 years ago. Lake Powell has dropped more than 30 feet in the last few years.

The water crisis is not limited to the Colorado River Basin. The most recent data from the U.S. Drought Monitor found that more than 50 percent of the entire contiguous United States is experiencing severe drought. And right now more than 75 percent of the Western region is seeing severe drought. These conditions threaten to put farmers and ranchers out of business, threaten the communities that rely on this water to support their families and their livelihoods, and frankly, threaten our way of life across the West.

States that divide the flow of the Colorado River. Image courtesy of Mission 2022 Clean Water.

Farmers like Joel Dracon, a dryland wheat farmer near Akron, Colorado. He told me he’s had to tear up 400 acres — nearly a third of his land — because there wasn’t enough water. He’s also had to sell a tenth of his herd because there’s not enough grass to graze his cattle.

Paul Bruchez is a rancher in Grand County, Colorado. He remembers when water from the Colorado used to flow at 6,000 cubic feet per second. Today, he said they’re lucky to have 1,000 cubic feet per second.

Harrison Topp, a fruit grower from the North Fork Valley, told me he’s lost “hundreds of thousands of dollars” in the last three years from drought. “There is no longer even a slim margin for error in our production practices,” he said.

A farmer in the same county, James Henderson, said it used to take one hour to irrigate his soil. Now it takes six hours, because the ground is so parched.

And the main reason for all of it is climate change.

Rising temperatures mean less snowpack in the Rockies, which means less runoff to feed our rivers. And that means less water for farmers, ranchers, and communities across the West.

And on top of that, the rising temperatures mean that whatever water makes it into our rivers evaporates and gets absorbed into the ground more quickly, because it’s so dry.

This is a five-alarm crisis for the American West.

When hurricanes and other natural disasters strike the East Coast, or the Gulf states, Washington springs into action to protect those communities. That’s what a federal government is supposed to do — to bring the full power and resources of the American people together to help our fellow citizens.

Firefighter crews from all across the country were involved in the 2019 Decker Fire. This photo, courtesy of pri.org, is of fire crews from Americana Samoa, who sing to stay motivated on the job.

But we haven’t seen anything like that kind of response to the Western water crisis, even though its consequences are far more wide-reaching and sustained than any one natural disaster.

And that’s just water. I haven’t even mentioned how climate change is incinerating our forests and blanketing our communities in smoke from wildfires.

Three of the largest wildfires in Colorado’s history were all in 2020. The day before New Years Eve, the Marshall Fire destroyed over 1,000 homes in Boulder County, Colorado in 24 hours.

Last year, communities in my state had some of the worst air quality in the world because of wildfire smoke.

There are days when people can’t go outside. They can’t open their windows. They can’t see the mountains. This dangerous air pollution puts Coloradans’ health at risk.

And it’s left people across the West to reckon with a sobering possibility — a future where this isn’t the exception; it’s the norm.

I deeply worry that if we don’t act urgently on climate change, it will make the American West unrecognizable to our kids and grandkids.

I refuse to accept that, and the people in my state refuse to accept it.

They have a reasonable expectation that our national government is going to step up and help protect the American West.

So my hope is that our hearing today will help shake the complacency from Washington and create the momentum we need to act urgently on climate.

And I’d like to thank our witnesses here today for sharing their expertise in this area. I look forward to hearing about what they are seeing and experiencing on the ground and the ways they are trying to manage this crisis.

We must act now to bring immediate relief to these Western communities. And we simply cannot address the Western water crisis in any meaningful way until we address the threat of climate change.

Recent Comments