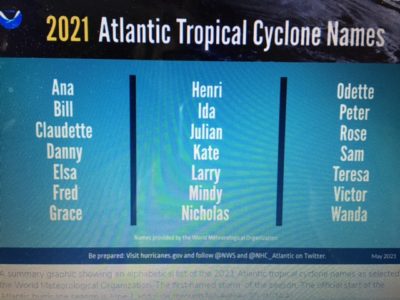

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is predicting another active hurricane season. The Atlantic hurricane season extends from June 1 through November 30. Although the actual hurricane season is still a week away, a tropical weather disturbance, named Ana, is already being tracked.

NOAA says that it is projecting the storm season coming off the Atlantic with a 70 percent confidence in its projections. For 2021, the prediction is for a likely range of 13 to 20 named storms (which means storms with winds of 39 mph or higher), of which six to 10 could become hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or higher).

Given the prevailing weather patterns, the forecast says we should expect three to five major hurricanes (storms rated category 3, 4, or 5; with winds of 111 mph or higher). The good news: NOAA isn’t predicting the historic levels of storms such as occurred in 2020.

“Although NOAA scientists don’t expect this season to be as busy as last year, it only takes one storm to devastate a community,” said acting NOAA Administrator Ben Friedman.

The globe is in a neutral phase (called ENSO-neutral) between the two weather patterns — El Niño and La Niña — that typically lead to shifts in our weather patterns. According to NOAA, there is a possibility of the return of La Niña later in the hurricane season.

“ENSO-neutral and La Niña support the conditions associated with the ongoing high-activity era,” said lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center Matthew Rosencrans. “Predicted warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds, and an enhanced west African monsoon will likely be factors in this year’s overall activity.”

Scientists at NOAA also continue to study how climate change is impacting the strength and frequency of tropical cyclones, which occur over the Pacific Ocean.

A generally-slowing jet stream is causing a wobble across North America, which is allowing weather systems to stall out over areas, leading to torrential moisture from single storms, and higher storm surges. In other areas, rising temperatures coupled with stalled-out weather patterns are preventing normal moisture and the monsoon seasons of the southwest, from reaching areas now moving into prolonged drought.

Recent Comments