In late May, I stood on the lip of Glen Canyon Dam, peering over the concrete edge to study the receding waters of Lake Powell. The reservoir was 75 percent empty.

Below, I saw what appeared to be railroad tracks in a bench along the canyon wall. Acting Dam Manager Gus Levy said they were remnants of a concrete batch plant created to construct the dam in the early 1960s. They had emerged in February, the first time in nearly 60 years they had been above water.

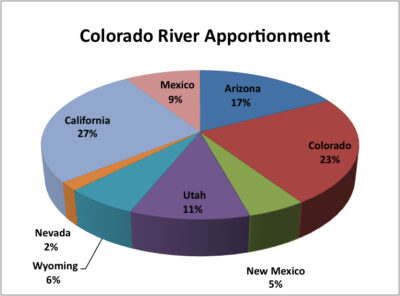

The 21st-century drought, now long and still deepening, coupled with aridification, has exposed problems in the compact governing allocations among the seven states in the Colorado River Basin. One clause in the Colorado River Compact would seem to saddle headwater states with taking up all the slack for reduced flows caused by climate change.

Now comes an important voice counseling a new view. Bruce Babbitt, two-time governor of Arizona and then U.S. Secretary of the Interior in the Clinton administration, says it’s time to revisit this obligation.

“While I once thought that these aridification scenarios were kind of abstract and way out in the future, I don’t think that anymore,” Babbitt said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s absolutely urgent that we start thinking now, while there’s time, about how we adjust the compact, the regulations, the necessary reductions, in the most careful way so that we limit the damage, which can really be extreme.”

“Huge,” tweeted Eric Kuhn, former manager of the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River District, after Babbitt’s remarks were published.

States that divide the flow of the Colorado River. Image courtesy of Mission 20212 Clean Water.

At the Getches-Wikinson Center at the University of Colorado law school in Boulder next week, a conference subtitled “Hard Conversations about Really Complex Issues” will take up just what will constitute the thoughtful approach that Babbitt advises. The river and its tributaries provide water for up to 40 million people and some of its most productive farms across seven states.

Delegates from the basin states who gathered in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1922 assumed the river would deliver roughly 20 million acre-feet annually. That was unjustifiably optimistic. Evidence already existed of climate swings. The 20th century mostly failed those expectations, and the 21st century has been even stingier, delivering 17 percent less.

Jeff Lukas, a climatologist based in Lafayette, Colorado who will speak at the conference, warns that even less water should be expected in coming decades.

“If forced to pick numbers right now, I’d go with 7 percent to 25 percent lower by midcentury and 13 percent to 33 percent less by the 2080s,” Lukas said.

An end of natural drought might improve water flows, he adds, but only so much. Multiple studies attribute roughly half of the declined flows to human-caused greenhouse gases.

“But you don’t need a dire view of the future to know that the compact’s hydrologic assumptions and subsequent allocations are unworkable going forward,” he says. “I think the last 22 years alone have demonstrated that pretty clearly.”

Since 2007, the basin states have been patching up the compact with new agreements. A new sense of cooperation and shared sacrifice has become evident. Still untouched is that heart-burning stipulation that Colorado and the three other upper-basin states “will not cause the flow of the river at Lees Ferry to be depleted about an average of 75 million acre-feet for any period of 10 consecutive years …”

A sharp photo of a nook of Lake Powell showing the reservoir depletion. It is fed by the Colorado River. MU

Lees Ferry is located in Arizona, above the Grand Canyon. Upstream 15 miles is Glen Canyon Dam, which generates hydroelectric power consumed in Basalt and Edwards as well as many other towns and farms in Colorado. However, the reservoir allows upper basin states to reliably deliver water to the lower-basin states and Mexico.

Brad Udall of Colorado State University’s Water Institute says the compact must be reinterpreted, not renegotiated. He believes delegates from upper-basin states who helped draft the compact a century ago would never have agreed to a fixed obligation in a changed climate. To assume so now also violates common sense.

The 19th century thinking was rooted in winners and losers, he says. Today, the intertwined economies of Southwestern states need solutions that maximize certainty even if the volume of water declines.

“The only thing that makes sense to me is that the two basins share this fundamental risk of declining flows, and I think that is a key part of a 21st century reinterpretation of the compact.”

Runoff from last winter’s snowstorms, if once again below average, has likely once again inundated those tracks I saw at Glen Canyon in May. They won’t stay submerged. Colorado River forecasters expect Powell’s resumed decline later this year. By January, it will be 80 percent empty.

Allen Best publishes Big Pivots, which focuses on climate change and attendant changes in energy, water and agriculture. See bigpivots.com.

Featured image: Glen Canyon Dam, Upper Colorado, with hydro electric power plant. Photo courtesy of the Bureau of Reclamation.

What about the 2 big alfalfa farms in Arizona, that are owned by the Saudi Arab, using the Colorado water , but paid for by taxpayers and alfalfa sent back over to Saudi Arabia for their cows .