Oceans and Coral Reefs are the Canary in this Global Coal Mine

Oceans and Coral Reefs are the Canary in this Global Coal Mine

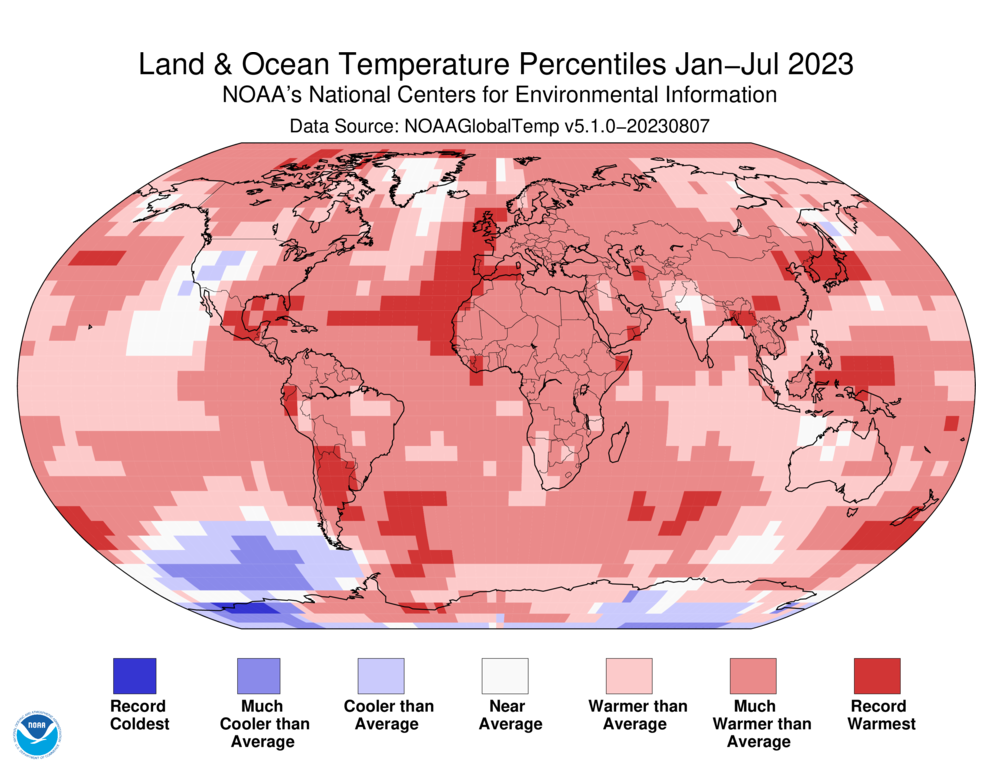

Not to sound like a broken record, but July set a record for the highest monthly ocean surface temperature in the 174-year history of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Look at the visual above. See much in the way of “near average” stretches of ocean?

Until now, the oceans have absorbed the heat, and this year it appears they can’t protect us any longer. If it feels as if there are more extreme weather events, all happening at once — you’re right — there are.

All of us on this planet have been born and grown up in a relative sweet spot in terms of climate — a golden age of predictable weather conducive to human and animal existence. That is in the process of changing.

We are seeing massive wildfires in Europe and across Canada, ocean temperatures off the coast of Baja California warmed even more by the effects of El Niño, a rare hurricane aimed at the west coast, massive flooding and rain events in New England, and heat domes stuck across the central U.S. — all happening at once.

According to the latest report of what is now known as the National Climate Assessment, we are in deep trouble. Some really smart people, scientists, and data gurus have been crunching the numbers and assessing the statistics and they have been creating a scientific assessment not just of what has already happened to our climate — but of what lies ahead for us, our children, and our grandchildren.

Here’s what this assessment says:

The Overview is Stark

1. The global climate is changing more rapidly than scientists thought it would — or could. Between 1901 and 2016, the average temperature went up 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, accelerating in the last couple of decades. There are no natural causes that can account for this; the evidence points to humans. The evidence says Earth’s climate is going to continue to change. The temperatures are going to continue to rise based on what we’ve already done to the atmosphere — it’s built-in. How much more though — is up to us.

2. Future Global Climate might be extreme. If we can severely limit fossil fuel use, we can maybe hold that rise to around 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100. If we don’t — we could see an average annual temperature rise up to nine degrees Fahrenheit over pre-industrial levels. That is not conducive to human life.

I don’t know about you – but I don’t want to be on this planet if that happens.

3. The oceans are losing their ability to absorb the excess heat we are producing from fossil fuels. As Ark Valley Voice wrote about a few weeks ago, until now, they’ve taken about 93 percent of that heat impact.

But this year our luck has run out. July set a record for the highest monthly ocean surface temperature in the 174-year history of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Translated — our oceans are becoming warmer faster, and they are more acidic, which means they hold less oxygen. This means species that live in the ocean are in trouble too.

4. Rising global sea levels of seven to eight inches over the past century might not seem like much — but oh boy — it is a big deal if you live on a Pacific Ocean island, or happen to own coastal Florida land. It means that every storm has the possibility of becoming more severe, with higher tides and stronger waves.

But sea level rise is just beginning. Between the year 2000 and 2100, scientists are predicting a rise of one to four feet of sea level. If unstable Antarctic ice sheets collapse, that rise could become eight feet; while eight feet is nothing in a mountain valley like ours, if you live on the coasts, you should start worrying.

5. Average U.S. temperature increases have accelerated — rising 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit since 1900; with 1.2 degrees Fahrenheit of that rise in the past few decades. At the moment a heat dome comparable to the record-breaking depression-drought year of 1936 has installed itself over the central U.S. — and it isn’t moving.

The predicted future is stark; even if we begin finally to address greenhouse gases, they will rise an average of 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit higher than 2000 in the next few decades, and between three and 12 degrees average by 2100 depending upon what humankind decides to do about it.

6. Extremes in temperatures and a stalling Jet Stream lazily looping across the country, translate to precipitation events that are heavier, and longer and more prone to stall out over a region.

Just as happened this past summer in New England, systems are projected to dump record levels of moisture as rain on the Upper Midwest, and Northeast, while reducing snowpack and surface moisture in the Mountain West and Southwest. With more moisture falling as rain, not snow, areas that traditionally count on a slow release of moisture are in for a big adjustment.

7. The Arctic is heating up. Nowhere on earth is this climate change and rapid temperature shift occurring more than in the Arctic. By mid-century, 2050 it is expected that the Arctic Ocean will be free of sea ice in summer. Permafrost is thawing and releasing huge quantities of carbon dioxide and methane.

8. Individual weather events are becoming more severe. New terms are being used to describe the extended extreme weather we are seeing: “atmospheric rivers”, tropical-strength rainfall moving west and north, tornados on the East Coast, polar vortexes in the Midwest, and since 1970, an increase in Atlantic hurricane activity.

It adds up to some areas seeing “the storm of the century” every decade, or a 1,000-year flood every few years.

9. Increases in coastal flooding. We live several thousand feet higher than the streets of Miami, which these days seem to flood with every rainstorm. Saltwater is inundating freshwater marshes, destroying critical ecosystems and habitat.

Since the 1960s, the entire East Coast has had to be concerned about flooding with high tides, as sea level rise has increased the possibility of flooding by a factor of five to 10 in coastal areas. It doesn’t take a hurricane. Even a tropical storm can cause massive flooding, as tropical storm Ida did on Long Island and Manhattan in 2021.

10. The planet is facing long-term changes. What we used to call “normal” appears to be receding into the rearview mirror. We are all headed into the unknown, with scientists as our best navigators for what will happen next.

Where is the Mountain West in the National Climate Assessment?

An interesting side note about the National Climate assessment is this — it lists 10 geographic regions — but there is no chapter predicting what is going to happen in the Mountain West. So what are we supposed to think? That there won’t be any impacts here at altitude? This of course is not true.

This year, the Mountain West has largely escaped the weather extremes, and this past spring the Front Range was inundated with rain. But as climate and energy tracker Allen Best noted in his August 16 column, “I’m uneasy. This is not normal. Weather varies, but our climates have been warming briskly. July was the hottest ever for planet Earth. When will it be our turn to be part of the bonfire?”

As to geographic regions, it appears we are lumped into the Southwest (an uneasy fit at best). Perhaps they have just dropped Colorado under the heading of our primary crisis — water.

The report tries to address our future in Number 6 (above), pointing out more moisture falling as rain, and decreased snowpacks leading to lower soil moisture. This of course continues our general drought and adds to the fire danger, which impacts local and state economies, quality of life, wildlife habitat, and a number of other things.

Even if the scientists aren’t focused on what this new extreme reality means for us — we residents need to think about it, plan for it, and get ready to deal with it.

What it means for us – the non-wealthy is harm until death, even here in Chaffee where businesses do nothing to protect residents from their pollution and never have. They do what they want and reap the rewards and then start saying they are going to be climate friendly after the damage is done to the poor. It is the same way all of the businesses causing us to have to flee our homes operate. They deny responsibility and simply cause death by refusing to look at the harm. Maybe there is hope still, but that would rely on enforcement. Given our problems the last 20 years with our neighboring businesses, enforcement is never going to happen around here, so lawsuits and rules need to be proposed to protect those of us impacted (and sacrificed) for our local businesses profit.

https://www.denverpost.com/2023/05/17/colorado-environmental-justice-dic-rules/