Invasive species may be hitching a ride on boats arriving in Colorado. Colorado’s lakes and reservoirs are free of invasive zebra and quagga mussels through Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s (CPW) Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS) prevention program, but in 2020 more boats than ever before are requiring decontamination due to infestations of the mussels compared to previous years.

This past year, ANS staff conducted a total of 647,325 inspections and 24,771 decontaminations of boats suspected of hosting mussels, invasive species, or standing water; a 34 percent increase from 2019’s inspections and decontaminations. 2020 saw 1,000 boats contaminated with mussels, while in 2019, only 86 boats were found to be infested, while inn 2017, only 16 boats were found to be infested.

“Last year we just saw record visitation, where people embraced getting outdoors and utilizing our vast recreational opportunities as an effective means of social distancing and remaining safe,” explains Robert Walters, an invasive species specialist and manager for the ANS program. “There is going to be a corresponding increase in the number of contaminated boats. Another aspect is that every year we continue to have more waters in our neighboring states that are becoming infested, particularly in the last several years.”

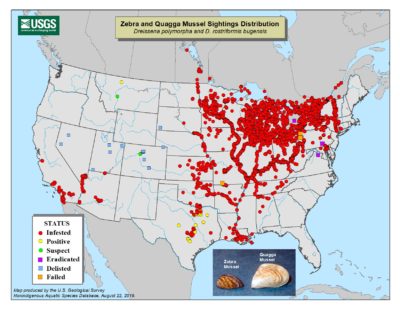

The vigilance in this state appears to be working. Colorado is the only state to go from positive to negative, delisting all its bodies of water from the list of America’s waterways infested with mussels.

The Problem with Mussels

Invasive species of any kind can have severe impacts, and mussels are no exception. First, a single mussel can produce up to a million juvenile mussels. If only 10 percent of those survive, there would be around 10 septillion mussels after only five years.

Additionally, mussels produce byssal threads, which attach to hard and semi-hard surfaces. If they attach themselves to water-based infrastructures, like water distribution systems or hydroelectric facilities, they can clog the flow, making it harder for water to actually move through the systems. They can also attach to native organisms, marine structures, and watercraft.

Lastly, a single mussel can filter up to a liter of water a day. When millions of mussels are involved, they begin filtering out nutrients from the water, which can impact the whole aquatic food chain. Increased water clarity leads to increased sunlight penetration, which may drive sport fish deeper to feed and make it harder to catch them. When the water level goes down, Walters explains, the beaches can become covered with mussels, making it nearly impossible to walk on the shore without cutting your feet, and then the beaches end up covered in rotting shellfish.

Recreating on infected bodies of water often results in those boats carrying the mussels back to Colorado. “Lake Powell, which is an impoundment on the Colorado River on the Utah and Arizona border, is a huge destination for Colorado boaters and unfortunately, they have become extremely infested with a lot of mussels,” said Walters. “Colorado boaters go out there routinely every single week, and unfortunately, any boat that is out there recreating on Lake Powell does have the opportunity to bring these mussels back in. Last year alone 70 of the 100 interceptions that we had here in Colorado originated at Lake Powell.”

Colorado is the only state to go from positive to negative, delisting all its bodies of water. This map, made by the U.S. Geological Survey in August of 2019, shows infested bodies of water in the country. From the Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database.

These invasive species of zebra and quagga mussels first originated in the Caspian Sea. They were originally brought to the United States, specifically the Great Lakes, in the 1980s on large transoceanic ships shipping goods from Eastern Europe.

“These large vessels very often take up what’s called ballast water, which is essentially water that they’re bringing into the boat to lower their center of gravity so they’re less susceptible to waves and currents and all those kinds of things you experience out there on the open ocean,” explains Walters. “The primary way that we see them moving here within the continental United States is on recreational watercraft, so people are putting their boats out there in the Great Lakes region. … And then when they go ahead and launch that boat in the next location there is the potential that they’re inadvertently introducing these species into the next body of water.”

While CPW has never found adult mussels in Colorado’s water bodies, they have found mussel veligers, the microscopic larval stage for mussels. They were first found in Pueblo Reservoir in 2008.

“If mussels do actually become established in the waters here in the state, there really is no opportunity for eradication or to remove them from the body of water,” Walters says. “So it just continues to be incredibly important that Colorado continues to take a proactive approach to make sure these things don’t get established in the first place.”

Decontaminating Boats is Key

A key step in that proactive approach is ensuring that all boaters, recreational or otherwise, take the proper steps to decontaminate their boats after each use.

“As long as people’s boats are cleaned, drained, and dried when they’re moving between water bodies, then they are significantly reducing, if not eliminating, the potential to transport zebra and quagga mussels as well as any other aquatic invasive species,” said Waters. “The state also has a mandatory inspection program if someone has had their boat on out-of-state water, if they’re entering a location where inspections are required, or if they’ve launched on infested waters. The decontamination process usually involves using incredibly hot water to remove any mussels from the watercraft. “We don’t use any soaps, bleaches, chemicals, or anything like that. we are just going to expose every surface and every piece of equipment that could have come in contact with the water to hot water…and that water alone is shown to be an effective method.”

In spite of the relative simplicity of keeping recreational watercraft clean and dry, ANS saw a record number of potentially infected boats this year. Walters feels that inconvenience and a lack of education may keep boaters from fully engaging with their role in the process.

“Sometimes we get off the water and we just want to go home and get on with our day and move on to the next thing, and we may not take the time that’s necessary to make sure that our boat is cleaned, drained, and dried,” he says. It can be as easy as pulling all the drain plugs to allow standing water to drain out or even visiting available decontamination services.

“Some boaters don’t know that they could potentially be moving these things around through something that may seem inconsequential, like a small amount of standing water on their boat,” Walters added.

However, there is an upside. As of January 1, 2021, CPW and their ANS program delisted Green Mountain Reservoir, making Colorado completely free of invasive mussels. Colorado is the only state in the nation to go from positive to negative, showing that education and inspection vigilence work.

Walters feels that education on the wide impacts of mussel infestations can help boaters of all kinds understand the importance of proper care.

“If we had an invasive mussel population become established here in Colorado, it would not just impact those that are recreating on the water, it would impact every citizen here in our state,” he says. “If one of our bodies of water [that is used for drinking] happened to become infested, there would be a significant cost to our water providers to clean up that infestation, and the water providers would not just be taking those costs upon themselves, they would be passing it on to the citizens of our state. Even if you’re not out there drinking water, you’re using the power that is being generated from one of our electrical facilities.”

“We’re all on the same team here,” Walters says, “and we want to work together to make sure that these species aren’t impacting our usage of our aquatic resources.”

For more information on decontamination and prevention procedures, as well as more information on infested bodies of water out of state, visit CPW’s website on invasive mussels.

Recent Comments