Water Shortages for Colorado River Reservoirs, and the Arkansas Voluntary Flow Program Ends

Tuesday, August 16, is D-day for the seven states along the Colorado River Basin to propose a plan to conserve two to four million acre-feet of water in the coming year. Whether they can agree and meet that deadline appears in doubt.

Chaffee County and the Arkansas River hit another D-day today: it marks the ramping down of the summer voluntary flow program on the Arkansas River.

“People don’t realize the importance of the supplemental water from the Colorado to the Arkansas,” said Chaffee Commissioner Greg Felt, who serves on not one but two Colorado water boards. “As of today, the Arkansas River will begin to return to the actual native flow. We’ve been at a flow rate of 700 to 750 [cubic feet per second or cfs] and by Friday, we’re going to get down to 400. People need to realize the arm of the Colorado River reaches across the divide.”

The basin states were given a federal deadline to draft a plan to save the Colorado River reservoirs, which are necessary to save hydroelectric power operations at the Glen Canyon and Hoover dams at Lake Mead and Lake Powell. These major reservoirs have each dropped nearly 200 feet over the past years of drought. Last year, the alarming rate of water depletion on the Colorado River downstream, caused a first-ever water call on the reservoirs within Colorado itself, including Blue Mesa and Flaming Gorge.

The four states of the Upper Basin work together, but each has a representative implementing policy within the borders of their own state. During the 60-day comment period, Colorado outlined five steps it is willing to take. As Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy General Manager Terry Scanga wrote in his July 14 column; Colorado has been doing our part for the past 20 years. Attempting to provide more water to the Lower Basin, “is like trying to fill a bathtub with the drain open.”

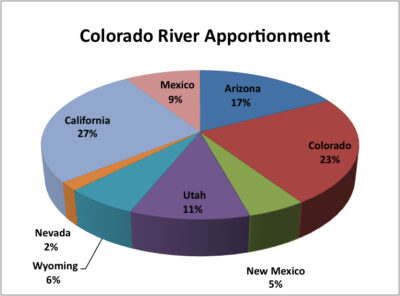

States that divide the flow of the Colorado River. Image courtesy of Mission 20212 Clean Water.

Given the fact that the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming have already been conserving more water than the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada, water experts say that the odds of an amicable agreement are moot. The Colorado River also provides a declining amount of water to Mexico.

“Do I think the Lower Basin is going to come up with actions to take in the next 24 hours? No,” said Felt. “What the Bureau did was get everyone’s attention. The Compact negotiators knew, but now this has got the country’s attention.”

No proposal means that the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is likely to step in. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton ordered the state plan last June. It appears likely that agriculture in the Lower Basin states will be the first to suffer water cutbacks.

“We may have just wasted 60 days,” added Felt, pointing out that to get real plans more measurable guidelines should have been set. “If you just tell a group of states to figure something out, everyone is going to look at each other to act. If they had set something measurable like everyone reduce by 10 or 12 percent…”

Four million acre-feet is a lot of water, and water experts say that on their own, the Basin states are unlikely to come up with that amount of sacrifice.

“At this point, a voluntary ‘2 to 4 million acre-feet of additional conservation’ Colorado River deal by Aug. 16 seems out of reach,” wrote New Mexico Professor John Fleck last week.

Fleck, a water expert, wrote that “four million acre-feet is obviously out of reach. It always was … the Upper Basin has said, ‘not our problem.’ Nevada’s share of the river is so tiny that its contribution is couch cushion change, a rounding error. That leaves, in round numbers, 1.5 million acre-feet of water to come out of Arizona just to get to Touton’s bottom line number for additional conservation. That would require completely drying up the Central Arizona Project canal.”

Fleck went on to point out that Arizona’s Native American communities have been completely cut out of the negotiating process, and they hold major water rights.

The Upper Basin states (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico.) do have an organized approach known as the Upper Colorado River Commission (UCRC). The UCRC suggested a five-point plan in July, along with a statement that said the Upper Basin states have already cut back on their water consumption and their options for doing more are limited.

These four states together are now estimated to use about four million acre-feet of water per year, under the 1922 Colorado River compact and legal water agreements of the last 100 years. Because their water use is above the major water reservoirs, in the recent drought years they have been limited by snowpack water flow; whereas the Lower Basin states have been dipping into the reservoir water reserves.

“Two million acre-feet of water is the range of the annual deficit now,” added Felt. “We’re buying time”

The Stakes Are as High as the Water Levels are Low

The Bureau of Reclamation’s most recent “minimum probable” model runs show Lake Powell dropping below its power level – meaning unable to generate electricity, and forced to move water through bypass tubes that Reclamation has made clear it does not trust – by October 2023.

Under that same Bureau of Reclamation model, Lake Mead drops to elevation 992 feet above sea level over the next 24 months — a level that will mean its power generation capability goes offline. It has not recorded this level since the reservoir began to fill.

Under the Colorado River Compact, which was developed during the wettest years of the last century, the three Lower Basin states share 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year; Arizona gets 2.8 million acre-feet; Nevada 300,000 and California 4.4 million. As of 2021, estimates show that the three states took 6.8 million acre-feet.

“The most drastic option would be the Bureau or the Secretary of the Interior, dictates a solution. More likely, if they had an answer now they’d have put it out there,” said Felt on Monday. “They’ll dictate a progression of meetings to try to force the collaborative effort, But this problem has festered so long … the train is headed toward a brick wall.”

What is increasingly clear, as the west’s long-term drought stretches into its 20th year, is that there are no major solutions, no silver bullets to get the states out of this. There are tough decisions ahead.

As Fleck added, “You can’t use water that doesn’t exist.”

Featured image: the Colorado River supplies the fast-shrinking Lake Mead. Image courtesy of Science Friday.

Recent Comments