Chaffee County Community Foundation Grant Recipients Speak as COVID-19 Need Continues

The voices of those profoundly impacted by our nation’s concurrent events, including the pandemic realities, deserve to be heard. Ark Valley Voice has set aside “Their Voices” as a special news coverage section, to encourage these voices to speak up, and to speak out. We believe it is important that this community understand how these experiences represent a reality that affects all of us. Some add their names to their stories, others speak anonymously. All deserve to be heard.

Her Voice:

“I didn’t feel judged, I just felt cared for and cared about.”

When Susann Swartz-Wright learned in April that she and her chronically ill husband would receive $1,000 from the Chaffee County Community Foundation, she says she was overwhelmed with gratitude. “I cried like a little girl,” said the 55-year-old Salida resident. “And that’s not like me.”

A month earlier, Swartz-Wright got laid off from Arkansas Valley Insurance Allstate due to the pandemic. While insurance was deemed an essential business under state pandemic policies, data privacy rules and other factors ruled out her working from home. Her unemployment check was minuscule because of a glitch in her work history, and she had no idea when she’d receive any federal benefits.

After a relative told her about the foundation’s Emergency Response Fund, she applied and within a week, the $1,000 was in her account. Without the grant, “my husband would have had to go without his medications.”

After a relative told her about the foundation’s Emergency Response Fund, she applied and within a week, the $1,000 was in her account. Without the grant, “my husband would have had to go without his medications.”

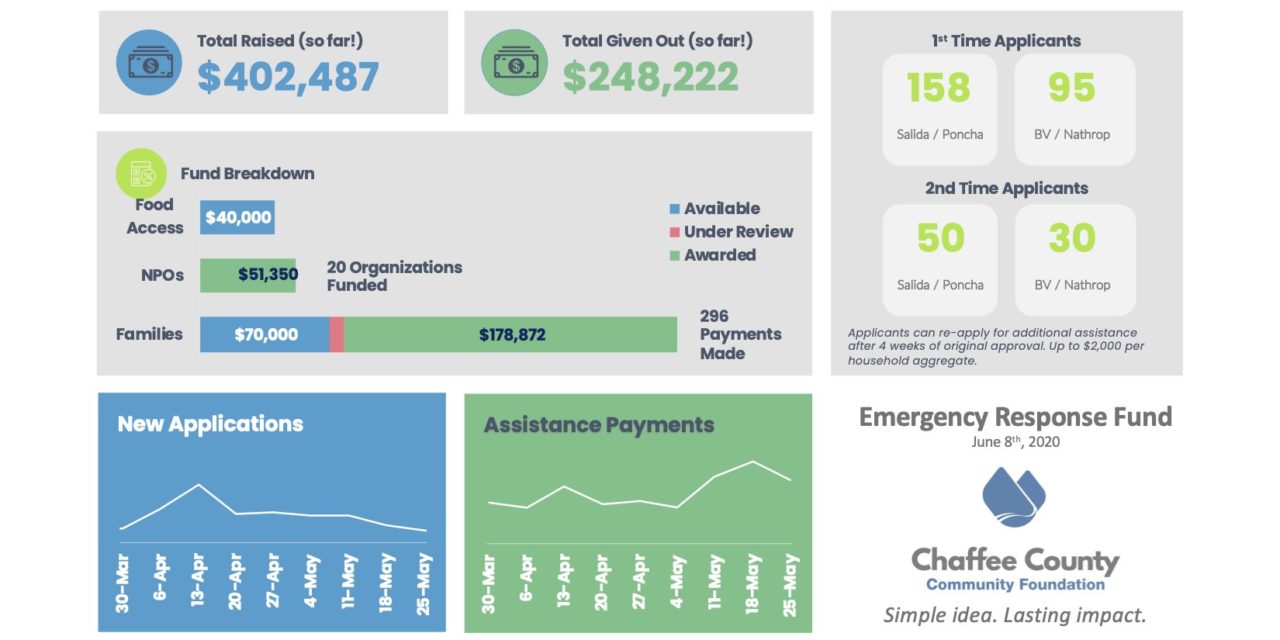

First established in 2019 to help people displaced by the Decker Fire, the Chaffee County Community Foundation’s Emergency Response Fund (ERF) was adapted to the COVID-19 crisis earlier this year; as of June 2, it had raised $401,680 and given out $230,722 to more than 250 individuals or families who were pushed into financial distress by the crisis but didn’t qualify for Colorado Department of Human Services emergency grants.

While the grant recipients’ personal identities are strictly confidential, Swartz-Wright and a handful of other Salidans agreed to share their stories. Some are employees who’d been laid off, while others are small business owners who were forced to shut down entirely or to scale back to a fraction of what their business had been before the pandemic.

Some have gone back to work, mostly part-time; but with one exception, none have recovered anything close to their former income levels.

More Stories:

“I’ve gone back to work, but only at 20 to 25 percent,” said Barbara Van Wyck, 60, who shut down her InterSynthesis physical therapy business in mid-March. She says that many of her clients are older and choosing to stay at home as much as possible. “Some are also out of work” and can’t afford physical therapy.

Like several others interviewed, Van Wyck thinks she may re-apply for another ERF grant. (Grants are $500 to $1,000, and a household can receive up to $2,000 in 2020.) “It remains to be seen what happens in the next month,” she said. “Just recently, I’ve had a lot of people cancel after [the local economy] started to open up [because] it makes them more nervous.”

Like all other applicants, she was interviewed by a foundation board member who also made the decision about her grant. She says that while asking for help was “humbling,” the board member made her feel comfortable. “I didn’t feel judged, I just felt cared for and cared about,” she said.

A 64-year-old Salida bookkeeper, who asked to be quoted anonymously, has lost 65 percent of her business and expects to apply for a second ERF grant, “just to be on the safe side. Every $10 or $20 helps me at this point. I managed to argue my Spectrum bill down from $121 to $94.” She is also receiving food stamps and recently applied for low-income energy assistance.

Two men in their 50s who received ERF grants after losing their restaurant jobs both expressed doubts that they’ll be able to work in that industry again, even with the phased re-opening.

“I’m pretty sure restaurant work in Salida is going to dry up for a while,” said Allen Newell, 59, who most recently worked as a cook. Asked what he expects to do for a living, Newell responded. “At this point, I have no idea. I just have to wait and see how this virus plays out.”

A 55-year-old former sous chef, who requested his name be withheld, is certain he will not be returning to his job.

“Even though the restaurant opened with limited seating, my boss doesn’t need me. He can get by with his own family members.” With support from a friend, he’s taking an online course in real estate. “I’ve been in food and beverage for many years, and I think it’s going to be a while before that business gets back to normal.”

Michael Henry Shelton, 35, was luckier with his job at Amicas Pizza Microbrew & More. When the pandemic was declared, the staff of about 35 was divided into three groups that worked four days on and eight days off. “The whole idea was to limit exposure between the staff and customers,” said Shelton. “I thought it was brilliant.”

Amica’s owner Michael McGovern explained that with this approach if an employee does get sick with COVID-19, “we’d be able to keep that whole group of employees out of the restaurant.”

Employee’s hours were reduced 50 percent on average, but Amica’s kicked in enough additional wages so that employees could qualify for the state’s Work-Share program, which pays partial unemployment benefits when someone’s normal work hours are cut 10 to 40 percent.

Shelton and his partner, an alternative medical practitioner who until recently lost 100 percent of her business, still needed help to pay their mortgage. “The grant eased my worries about getting behind on our house loan,” he said.

David Haynes of Fantasy Games and Comics 150 West First Street in Salida with Shasta (l) and Wichita (r). Merrell Bergin Photo

Around the corner from Amica’s, Fantasy Games & Comics on First Street was shuttered in March along with other non-essential retailers. Owner David Haynes says he was able to earn some income after that from online sales. He recently re-opened with one part-time employee; but with the store’s revenue at only about 20 percent of what it was before March, he also applied for a second ERF grant.

“I used the first one to eat and pay other living expenses,” he said. “It was a big help.”

Swartz-Wright received a second $1,000 grant in May. Like the first grant, this one went to groceries and to cover the $500 to $700 out-of-pocket portion of her husband’s doctor’s visits and medications. She started receiving better unemployment in May, and then more recently returned to work full time.

As she rebuilds her financial well-being, she expects to look for ways to repay the generosity of her fellow Chaffee County residents who contributed to the emergency fund. “I honestly believe that without this money, there are people out there who wouldn’t have survived,” she said.

“We at CCCF are humbled and honored to be trusted both with the amazing financial generosity of Chaffee County residents contributing to the ERF, as well as the trust and confidence of community members who’ve asked for help after being financially impacted by COVID,” said CCCF Executive Director Joseph Teipel. “We know that it can be harder to ask for help than to give it, so we take this responsibility very seriously.”

Stories Presented by Jim Hight

CCCF volunteer writer

Recent Comments